Defensive Medicine Supersedes Quality Medicine

June 29, 2010 12 Comments

A recent article in US News and World Report, Most U.S. Physicians Practicing ‘Defensive Medicine,’ claims that physicians are ordering more tests and escalating the work-up of sick patients, all in the name of defensive medicine. Is it true? Absolutely. It is especially true in the emergency department, where we have one shot to get things right, or else. Ironically, by practicing defensive medicine we are not practicing quality medicine – and isn’t that what patients really want? Training during residency has changed over the last two decades, and the emphasis has shifted from performing a good history and physical examination to ordering and interpreting laboratory tests and imaging studies. We no longer take the time to listen to our patients. Instead, we have started clicking as many buttons on the computer order set as we possibly can in order to cover every life-threatening diagnosis. But even in the world of technology, numbers, and images, medicine remains an imperfect science.

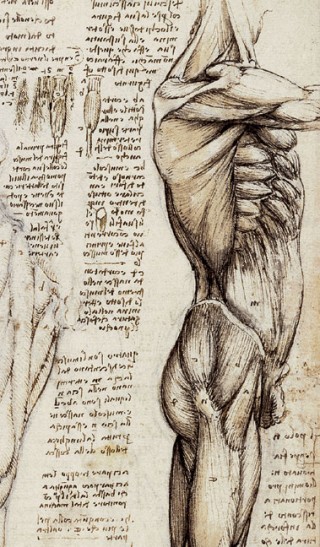

I vividly remember a lecture during medical school on cardiology. The professor, who was in his 80s at the time, taught us how to use the stethoscope and explained the subtleties of different heart sounds. He gave us a CD, which is now sitting somewhere in my closet under a film of dust. There is an art to distinguishing a rub, ejection murmur, opening snap, split S1, gallop, click, or extra heart sound – especially when the sounds are so soft that they can barely be heard in a completely silent room. It takes extensive practice and training to improve at this – but rather than using our stethoscope, we spend time looking at echocardiograms and troponin levels. As another example, there have been several articles written on how poorly residents and attendings perform a neurologic exam in the emergency department – a good neurologic exam takes time and requires the full, undivided attention of a perceptive clinician. Some people have a knack for this and others do not – regardless, physician training in these areas is far from what it used to be. Over the last year, I can count on one hand the number of times I have been accompanied at the bedside by an attending who lays his hands on the patient.

Our predecessors were better able to gather essential pieces of clinical data from a physical exam because it was the single tool they had. In the 1960s surgeons could only use their hands to diagnose appendicitis. The advent of new medical technology, various imaging studies, and more laboratory tests has been both helpful and detrimental – for it has allowed us to gather more information for diagnostic purposes, but it has also given the wrong impression that this information is more “certain” than or is a substitute for the physical exam. Laboratory tests and imaging studies, just like the physician’s own hands, are an imperfect science. Although the perception is that patients benefit by getting a myriad of lab tests and imaging studies, they do not. These tests have as many limitations as the history and physical exam, and they only gain their significance when analyzed by a physician in the broader clinical picture.

Rather than accepting the inherent limitations of tests, clinicians have begun to practice test-centered medicine rather than patient-centered medicine. This causes huge delays and expenses in patient care. It also places patient at risk for (1) being treated unnecessarily for incidental findings and (2) being exposed to unnecessary radiation. Furthermore, it alienates patients even further from their physicians – and this, perhaps, is the greatest cause of increased lawsuits and patient dissatisfaction, which starts the cycle of practicing defensive medicine all over again.